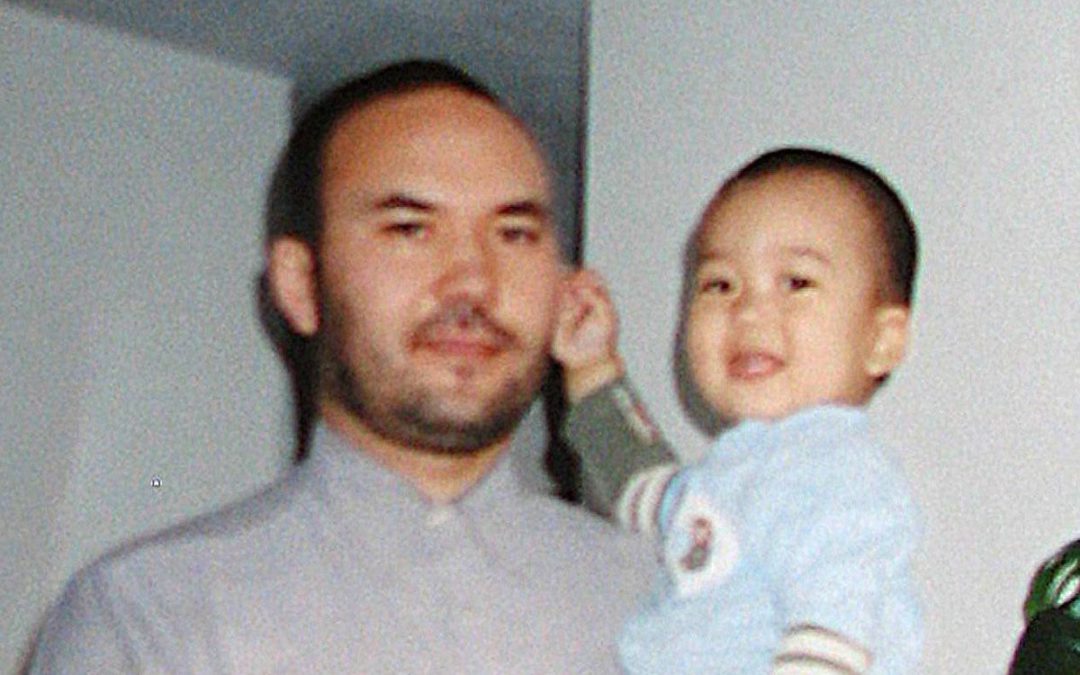

Languishing behind prison walls somewhere in China, Huseyin Celil may never know how much impact he has had on the continuing plight of a group of his brethren held in a controversial prison on the other side of the planet.

The Globe and Mail has learned that the Canadian government came very close to accepting as refugees a group of Uyghur prisoners from Guantanamo Bay – men who were captured by bounty hunters in Pakistan six years ago, handed over to American soldiers, shipped off to Guantanamo and then almost immediately found to have done nothing wrong.

But Ottawa pulled back at the last minute, in large part, sources say, because of fears of what would happen to Mr. Celil, also a member of China’s Uyghur minority, if the transfer went ahead – Beijing has lobbied furiously to keep any nation from accepting the Guantanamo Bay detainees.

Interviews with government and legal sources, as well as documents obtained under the Access to Information Act, show the political negotiations that went on behind the scenes, as the U.S. desperately tried to get rid of men it now admits pose no threat.

Those men might well be Canadian residents today if it weren’t for another imprisoned Canadian whose release Ottawa is unable to secure.

POLITICAL FAVOURS

In 2002, a few months after the U.S. invaded Afghanistan, bounty hunters across the region were rounding up anyone they could hand over to the American military, usually for a handsome sum – an arrangement the military frequently accepted.

Among those men were a group of almost two dozen Uyghur men captured in Pakistan. The Uyghurs are a Muslim minority group in northwest China. Since Sept. 11, 2001, Beijing has used the war on terrorism as leverage in its continuing crackdown on the Uyghurs, some of whom have fought fiercely for independence from China.

The men were handed over to the U.S. military for about $5,000 a head, and eventually flown to the newly established detention facility in Guantanamo Bay.

It quickly became clear to U.S. officials that, if the Uyghurs harboured hatred against any government, it was that of China, not the United States. The men denied allegations of wrongdoing, and it wasn’t long before then-secretary of state Colin Powell was looking for a country to take the prisoners.

“The U.S. recognized very early on that these men were captured by mistake,’ said J. Wells Dixon, an attorney with the New York-based Center for Constitutional Rights, who represents some of the Uyghurs.

Although some of the detainees were cleared for release from Guantanamo Bay as early as 2003, it was not until 2006 that any of them actually left the naval base.

The timing of the men’s release was coincidental at best. Some of the prisoners, who had earlier been declared “no longer enemy combatants,” had filed court cases arguing the U.S. could no longer detain them. A U.S. court of appeal was set to hear arguments in the case on May 8, 2006. Three days before the hearing was scheduled, the five men were released from the base and flown to Albania. The court case was dismissed, and Washington avoided a ruling on whether what was happening in Guantanamo was legal.

Albania, which has no Uyghur community to speak of, was far from an ideal location for the men. Indeed, the U.S. had quietly (and unsuccessfully) lobbied about 100 countries to take the prisoners. Among those countries was Canada, a place the prisoners’ lawyers had hoped would agree to take them in. Albania was the lone outlier among those countries, and not for purely benevolent reasons.

“It appears to us that they were sent to Albania because Albania owed the U.S. a political favour,” said Mr. Dixon. “Albania wants very much to become a part of the European Union. … As soon as [the Uyghurs]were sent to Albania, it was shortly thereafter that the U.S. announced support for Albania’s efforts to join the European Union.”

It is also believed that the U.S. paid millions of dollars as part of the transfer agreement.

But the factors were not the same with other countries. Many did not want to take men who were in any way associated with the controversial detention facility. Many questioned why Washington wouldn’t allow the men to settle in the U.S. (something that would have had serious political and legal implications on the already controversial Guantanamo Bay facility).

But perhaps the most significant factor in the widespread refusal to accept the men had to do with Beijing’s lobbying. The Chinese government made it clear that it considers any such transfers to be violations of international law, and wants the men instead sent to China. But the U.S. has refused to send the men back because of the likelihood they would be tortured. In an ironic twist, the U.S. was now put in a position where it had to protect men it once accused of heinous crimes from potentially heinous treatment.

Judging by how many nations refused to take the prisoners, China’s lobbying appears to have been at least partly successful. But in Ottawa, Beijing’s position carried even more weight.

CRACKING UNDER PRESSURE

On May 18, 2006, a U.S. delegation met with senior political staff at the Department of Foreign Affairs, Citizen and Immigration Canada, the Canada Border Services Agency, the Department of Justice and the Prime Minister’s Office. The purpose of the high-level meeting was to discuss the Uyghurs.

It was not the first time the U.S. had asked for Canada’s help. Washington had sent specific requests about the Uyghurs to Foreign Affairs, CIC and the Privy Council office in October, November and December of 2005.

Documents obtained under the Access to Information and Privacy Act show that Canadian officials at the May meeting indicated the prisoners would likely be inadmissible under Canadian immigration law, but did not make a firm decision.

“There has been no decision by the Government of Canada as to whether to formally discourage or encourage the US from making formal referrals for resettlement pursuant to the Canada-US Safe Third Country Agreement,” a briefing note reads.

Under the agreement, anyone seeking refugee protection must make a claim in the first country they arrive in – be it the U.S. or Canada – unless they qualify for an exception. The situation may be more complicated in the case of Guantanamo Bay, a place that Washington has gone to great lengths to treat as a separate entity from the U.S.

“[The Department of Foreign Affairs]will need to consider the bilateral and multilateral implications” of any transfer, the briefing note reads.

Government officials were instructed not to talk about the potential transfer. Officials were to say that privacy legislation prohibits them from discussing specific immigration or refugee applications, but that “Canada has an active immigration and refugee program. Individual resettlement requests are assessed on a case-by-case basis.”

Around the same time that Washington and Ottawa were discussing a potential transfer, Mr. Celil was travelling to Uzbekistan on his newly acquired Canadian passport to visit his wife’s family. While applying for a visa extension in March, he was arrested. On June 26, despite initially denying any knowledge of the case, Uzbek officials informed their Canadian counterparts that Mr. Celil had been handed off to Beijing.

Almost immediately, Ottawa worked to release the detained Canadian, taking his case up at the highest level with even the Prime Minister involved. Among the myriad consular cases, this one was a priority, and that meant stopping anything that could make Mr. Celil’s situation worse. The transfer of Uyghurs from Guantanamo Bay, once a very real possibility, was pulled off the table.

“My impression is that there was reluctance on the part of the Canadian government to do anything to further complicate their discussions with the Chinese government about Huseyin Celil,” Mr. Dixon said. “In other words, that there was concern that if Canada accepted the Uyghur prisoners from Gitmo that that would anger the Chinese and it would potentially complicate efforts by the Canadian government to get Huseyin Celil released.”

A source in Ottawa confirmed that Canada came very close to accepting the Uyghur prisoners, but ultimately backed off, in large part because of fears about how such a move would affect Mr. Celil’s condition in China.

But if the refusal to accept the Uyghurs as refugees was meant to make the Celil negotiations go more smoothly, it failed. In April of 2007, Mr. Celil was sentenced to life in prison for terrorism offences – offences he strongly denies and Canadian officials said they’ve seen no evidence of. Mr. Celil has had no access to Canadian consular officials. Beijing refuses to accept his Canadian citizenship.

NOWHERE TO TURN

Today, both Mr. Celil and the Guantanamo Bay Uyghurs have little reason to be optimistic. Both remain in controversial prisons. Despite being declared a non-threat, the Uyghurs are kept in Camp Six, the highest-security detention facility in Guantanamo, where inmates are isolated for 22 hours a day. Mr. Celil is believed to be in a prison in northwest China, but his family is no longer certain of his exact location.

In a way, both governments responsible for the detention of the Uyghurs and Mr. Celil have not changed their positions. Beijing has made it clear that it will not budge in Mr. Celil’s case. And fearing that further protest may affect other aspects of the China-Canada relationship, Ottawa has toned down its efforts to bring the imprisoned Canadian home.

Washington, too, has not changed its position. The U.S. continues to lobby its allies to take the Uyghurs, who make up a significant portion of the 70 or so men that the U.S. deems not a security threat. Since all three remaining presidential candidates have indicated their desire to close the facility, the U.S. is desperate to get as many of those 70 as it can out of Guantanamo Bay.

“My impression is that if Canada announced that it would take the Uyghurs on Monday, they’d be in Canada on Friday,” Mr. Dixon said.

Written by: OMARL EL AKKAD

Original Link: theglobeandmail.com/news/world/celil-guantanamo-bay-and-the-rejected-refugees/article18451290/

Recent Comments